Title: Bonds of Love and Blood

Author: Marylee MacDonald

Publisher: Summertime Publications Inc.

ASIN: 978-1-940333-08-3

Pages: 230

Genre: Literary Fiction, Short Stories

About the Author

Marylee MacDonald is a former carpenter, prize-winning author, and writing coach. The stories in her forthcoming collection, BONDS OF LOVE & BLOOD, have won the Barry Hannah Prize, the Ron Rash Award, the American Literary Review Fiction Award, the Jeanne Leiby Award, the Matt Clark Prize and other honors. Her novel, MONTPELIER TOMORROW, was a finalist for the Eric Hoffer Award, the Faulkner-Wisdom Prize, the 2015 Next Generation Indie Awards, and the Bellwether Prize. She lives in Tempe, AZ.

Questions:

Today we are talking to Marylee MacDonald, author of “Bonds of Love and Blood”.

PBR: Wonderfully written stories: insightful, lucid, and real. I found the attention to the intricacies and subtleties of human communication (passive-aggressive retorts, gestures, and so on) really intriguing. And with so many different relationships, I wonder if these insights come from personal experience or are you in fact a therapist of some kind, because the observations in many of these stories seem so spot on.

MM: I’m smiling at this question because I’m no more a therapist than anyone else who has glanced at the occasional pop psych book. First and foremost, I am a mother and a daughter, a wife and sister. I’m seventy as of September, and a grandmother many times over. Some of these stories originated with my own long and complicated life. Central to that life are issues having to do with loneliness and displacement.

PBR: “Weekend in Baltimore” really drew me in and I think it is because of its relevance to the race discussion going on right now in America. Did the inspiration for this story come from this recent discussion? And, whether it did or not, can you speak a bit about said discussion?

MM: No, I wrote the story ten or twelve years ago. I interviewed a guy who’d been thrown in the slammer in Baltimore, a friend of the family dismayed at his wrongful arrest. I viewed my role as a “debriefer.” Of course, once I heard the details of his weekend in Baltimore—the specifics of the food and drink and the jail cell and seeing the Commissioner—I thought, I should write about this so that other people can understand why wrongful arrest is so enraging and racism so debilitating.

In the days of my youth, the country as a whole needed to deal with voting rights and access to education and housing. This was simply to end the de facto segregation that existed everywhere, not just the South. Now, however, we need to deal with the legacy of those years and the quick judgments we make about other people, based only on skin color or ethnicity.

PBR: Although not always, relationship problems are the result of communication breakdowns, and this seems to be the case in “Finding Peter,” the story about a mother trying to literally locate and mentally connect with her adoptive son. Can you talk about this idea, relative to this story or others; that is to say, how generational and cultural gaps are still barriers?

MM: Yes, why do these gaps between people arise? What binds us together and what drives us apart? Like the son in “Finding Peter,” I was adopted. Over the years I have expended a lot of emotional capital trying to figure out where I belong. But, I am also the mother in that story yearning for a biological child and keeping hidden from her son the devastating loss of her three miscarriages. Often, our deepest pain is the very thing we find hardest to speak about. We may only be dimly aware of it ourselves.

I hope readers will notice the epigraph written by Bertrand Russell: “Love is something far more than desire for sexual intercourse; it is the principal means of escape from the loneliness which afflicts most men and women throughut the greater part of their lives.” When I read that, I thought, yes, that’s what these stories are about—the affliction of loneliness.

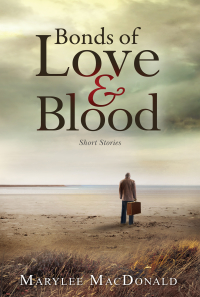

The cover of the book depicts a man standing on a seashore. He’s the elderly Japanese father, Mr. Tanaka, in the “The Ambassador of Foreign Affairs.” He’s bringing an old-fashioned leather suitcase to his daughter’s wedding. In addition to his shirts and travel documents, he’s carrying his loneliness and vulnerability.

PBR: “Proud to be an American” – another great story. It reminded me of older stories like Jack London’s “South of the Slot.” I felt like this was an interesting portrait of this binary opposition in America of the right vs. the left: in particular, the opposition of unions vs. individual entrepreneur. Was this your intent? And can you comment on what I thought was an ending showing the lure of greed?

MM: I’m so glad you like that story. Let me tell you a little about where it came from. I was teaching at a junior college in Champaign-Urbana. Many of my students lived on family farms of 650 acres or less. Farmers were going bankrupt because of agricultural policies. Ex-farmers couldn’t make sense of why their lives had turned upside down.

They seized on the idea that the Trilateral Commission had concocted a conspiracy to eliminate the family farmer and the American way of life. One of the kids in my English class sat slumped down in his seat. He didn’t want to be there, so I finally told him to drop the class and go get a job. He later told me the job he’d found. He was working as a mall remodeler. I, of course, worked for many years in construction, so I knew about slat-wall and laser levels. (This may or may not be relevant, but at one time, I was a Contributing Editor for Carpenter magazine. I knew about the union’s policies, including recruitment.) So, that’s the “real life” version.

Throughout the story, the main character Billy was this big lunk of a guy who carried the legacy of his father’s failure. At the end he found a way to make himself feel smarter and more important than he could be in real life. Just writing his full name—not “Billy” but “William Dwight Ripplemeyer,” plus his fake credentials—allowed him to escape into an alternate version of himself. That change completed the story’s arc, which began with a line on the first page. “There had to be a way that he could get from the life he had now to another life he couldn’t quite imagine.” By the end he can imagine that other life. Whether he can ever get there is another story.

PBR: These stories gave me a sense of modern short fiction but also classics such as those by Fitzgerald, Flannery O’Connor and others (perhaps because this is who I’ve also been reading lately). I’m really intrigued by who your influences are/were: classic and modern.

MM: Oh, gosh. Well, certain writers for certain things. Jane Austen for crowd scenes and getting people in and out the door. F. Scott Fitzgerald for sentences. Gina Berriault (Women In Their Beds) for sentences and character complexity. You may not know her work, but she was a National Book Award winner and deserved wider acclaim than she ever received.

To continue. Sigrid Undset (Kristin Lavransdatter) for the epic sweep of a life, young to old. I owe a great debt to Flaubert, of course, for the underlying passions that govern our lives and for permission to be the characters I’m writing about. “Madame Bovary, c’est moi.”

Henry James and Chekhov showed me the importance of recording the ephemera of life so that these details could later be incorporated in a story.

The work of contemporary writer, Margot Livesey, has taught me a great deal about the tiny moments of “perterbation” that occur as the reader’s eye passes down the page. These moments happen on a very subliminal level, but their cumulative effect creates great tension.

Anne Tyler’s novels have taught me about narrative tension. Toni Morrison’s work has shown me how baggage from the past can break open a plot. I owe Tim O’Brien for the hand-slap that taught me to avoid “ing” words. Wright Morris, my long ago mentor, told me that I wrote beautiful sentences and showed me the worthy dramas of life on the Plains. I am indebted to Annie Proulx for a lecture she gave at a high school in the Chicago area. She pointed out how locating characters in a setting that maximizes their discomfort works magic for a plot.

When I find a writer whose work I admire, I want to read everything they’ve written. I want to see where they began and what kinds of discoveries they’ve made. A writer I’m doing that with right now is the fabulous Billy O’Callaghan. Creative writing classes emphasize that “a character in a room alone” is death to a story, but in Billy O’Callaghan’s story collection, The Things We Lose, The Things We Leave Behind, characters spend a great deal of time wandering the attics of their minds, and it’s always fascinating.

I read very slowly and I pay attention.

To learn more about “Bonds of Love and Blood” please read the review at: Read Review