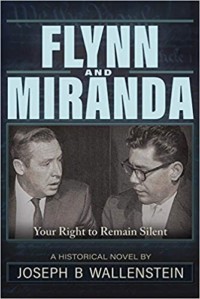

Title: Flynn and Miranda: Your Right to Remain Silent

Author: Joseph B. Wallenstein

Publisher: TrineDay Fiction

ISBN: 978-1-63424-311-7

Pages: 180

Genre: History

Reviewed By: Dan MacIntosh

Pacific Book Review

To be honest, most of us likely first learned about ‘Miranda Rights’ from watching TV cop shows and crime movies. Hopefully, few of us heard this disclaimer from a law enforcement officer while being arrested. You might even think this statement, which begins familiarly with, “You have the right to remain silent,” has always been a routine police practice. However, this verbal reminder of a suspect’s rights didn’t come into being until June 13, 1966. For many of us, this happened during our lifetime. Like many human rights issues in the United States, this arrest practice stems from a Supreme Court case, Miranda v. Arizona. With Flynn and Miranda: Your Right to Remain Silent, Joseph B. Wallenstein tells us the story behind this well-known Supreme Court ruling.

One of the Supreme Court’s primary duties is making sure every American law is constitutional. The Supreme Court is not concerned so much with the goodness or badness of the individuals involved in the various cases it hears. This Miranda v. Arizona case mainly involved attorney John Flynn and defendant Ernesto Miranda. Although history looks back on Flynn as the hero of this story, the man that argued this case before the Supreme Court and is portrayed in this book, is by no means painted as some squeaky-clean justice warrior. Wallenstein, who recounts this case and the events that led up to it in this story, pulls no punches when describing Flynn’s lifestyle. He’s a chain-smoking womanizer who will likely never win any ‘dad of the year’ awards. Similarly, Miranda is portrayed as a lifetime criminal. Lastly, the Arizona police officers involved in the case may have good intentions – that being ridding the streets of crime – but it’s their cruel ‘by any means necessary’ methods of getting criminals like Miranda convicted, are what ultimately convince Flynn that the Supreme Court is needed to right these law enforcement wrongs.

Wallenstein does a good job of humanizing these various participants. Flynn, for instance, is a flashy, attention-seeking lawyer. He’s not liked by some in his hometown community, including law enforcement and the Arizona Republic newspaper. Even so, those that dislike Flynn reluctantly respect him. With all his personality flaws, he’s nevertheless good at what he does. While Wallenstein’s viewpoint reveals empathy for Flynn, it doesn’t express the same grace for Miranda or the Arizona police. If there are bad guys, these are the bad guys in this tale.

One challenge Wallenstein handled nicely, was in keeping the reader compelled by the story, even though we already knew how it ended. His book answers a lot of questions about how this essential decision eventually came to be. Instead of just the facts, ma’am – so to speak – Wallenstein draws us into history by telling us a fascinating story.

Appendix A of this book is an extensive interview with Flynn. Appendix B is a series of photocopied documents from the court case. Both additions are worthy inclusions and add to the reader’s understanding and appreciation of this historic period.

It should come as no surprise to anyone that Wallenstein has also worked in production capacities on such popular films as The Godfather and American Hot Wax. He writes this story with an unmistakable cinematic eye. In fact, it’s easy to imagine this story filmed as a Hollywood Film Noir. It delves deeply into the criminal world, where not all the good guys are all good, nor are all the bad guys completely bad. Best of all, Wallenstein makes history come to life. Unlike some of those boring history classes we were forced to live through as young people, this book is so much more than a series of significant names and dates. Instead, Wallenstein puts flesh and bones on history, and leaves the reader convinced of this case’s utter, indefinite relevance.