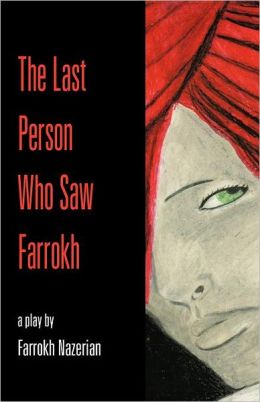

Title: The Last Person Who Saw Farrokh

Author: Farrokh Nazerian

Publisher: Osborn Publications

ISBN: 978-0-9849389-0-2

Pages: 104, Hardcover

Genre: Fiction (Play)

Reviewed by: Brandon Nolta, Pacific Book Review

Book Review

Ever since Shakespeare first put Hamlet’s plot against his uncle Claudius to paper, readers and performers have known that the play’s the thing, even beyond catching the conscience of a king. Plays can be used to entertain, to illuminate, and even to instruct the audience on matters great and small. With The Last Person Who Saw Farrokh, the latter two goals are the main objectives, portraying one man’s struggle with discovering his destiny and the effect this struggle has on those around him.Primarily told from the viewpoint of M, a woman whose love for the titular character borders on the obsessive, the play follows her efforts to find Farrokh, searching her memories for their last encounter and seeking clues to his absence in those recollections. As she wanders through a landscape both external and mental, she meets other figures in Farrokh’s life – a business partner, a group of revolutionaries, even Death – and continues to parse the sometimes contradictory statements and actions of Farrokh, all in hopes of being reunited with him.

From the previous plot description, The Last Person Who Saw Farrokh may sound like some kind of romantic escapade, but in structure and tone, it more closely resembles Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, which similarly trafficked in mundane dialogue, absurdist exchanges and seemingly inconsequential events. However, Nazerian’s play has loftier goals in mind, and the fact that the play is upfront about these goals works against it. Surprisingly for a play that relies strongly on symbols for its dramatic drive, the dialogue is too literal, with the themes and ideas that should underlie the play being left out in the open, so to speak, for all to see. The directness of the dialogue, despite the elliptical delivery that most of the speaking parts use (particularly Farrokh himself), makes it difficult to accept the world of the play; on the page, it reads more like a lecture on one person’s thought processes than a dramatic exploration of same, which drains much of the interest from the words.

In fairness, some of the on-the-nose nature of the dialogue is due to its presentation. Plays are not meant to be read as books; they should be performed to an audience, and having people deliver the dialogue with the weight of craft and experience behind it would alter its impact considerably. However, much of the dialogue is utilitarian in nature, rather than poetic or geared for performance. It describes, but does not take flight in the act of description, and sits on the page rather than perking up in the ears. When reading a play from playwrights at the top of the form – a list that ranges from Shakespeare to Stoppard, from Wilson to Mamet and any number of others – readers can usually pick up on a sense of rhythm, a near-musicality to the words and sentences that makes the delivery on stage more potent than what the text alone offers. Despite the ideas on display here, and the laudable ambition it took to pursue these ideas, this sense of musicality is absent, and the reading experience suffers for it.